A fight breaks out in A Commons during lunch. You and your friends get up from your table to see what’s happening, and you see a huge mass of other students watching, CSAs trying to get involved, and glowing phones filming the fight. But instead of high school administration and CSAs handling it, two police officers do. Those officers are armed, and they have the power to directly refer students to be arrested by the Charlottesville Police Department.

A scene like this could really happen at Charlottesville High School next year.

Student Resource Officers, also known as SROs, will return to our halls in August for the 25-26 school year. So far, CHS administration has already implemented some security measures this year, such as putting alarms on all of the school’s easily accessible doors. However, reinstating SROs will be a much bigger change.

According to Education Weekly, “school resource officers are “sworn law-enforcement officers with arrest powers”, and ours will work directly with the Charlottesville Police Department. “Almost all SROs are armed (about 91 percent, according to federal data), and most carry other restraints like handcuffs as well.”

This won’t be the first time CHS students have seen armed officers in our school. Between 2016 and 2020, two SROs were stationed here, and became a huge source of division for our school district. However, after the pandemic, the agreement between the City Schools and the Charlottesville Police Department dissolved. The Black Lives Matter movement was also an important reason for the decision: C-Ville Weekly reports the “anti-police brutality protests that occurred that year” as a main factor.

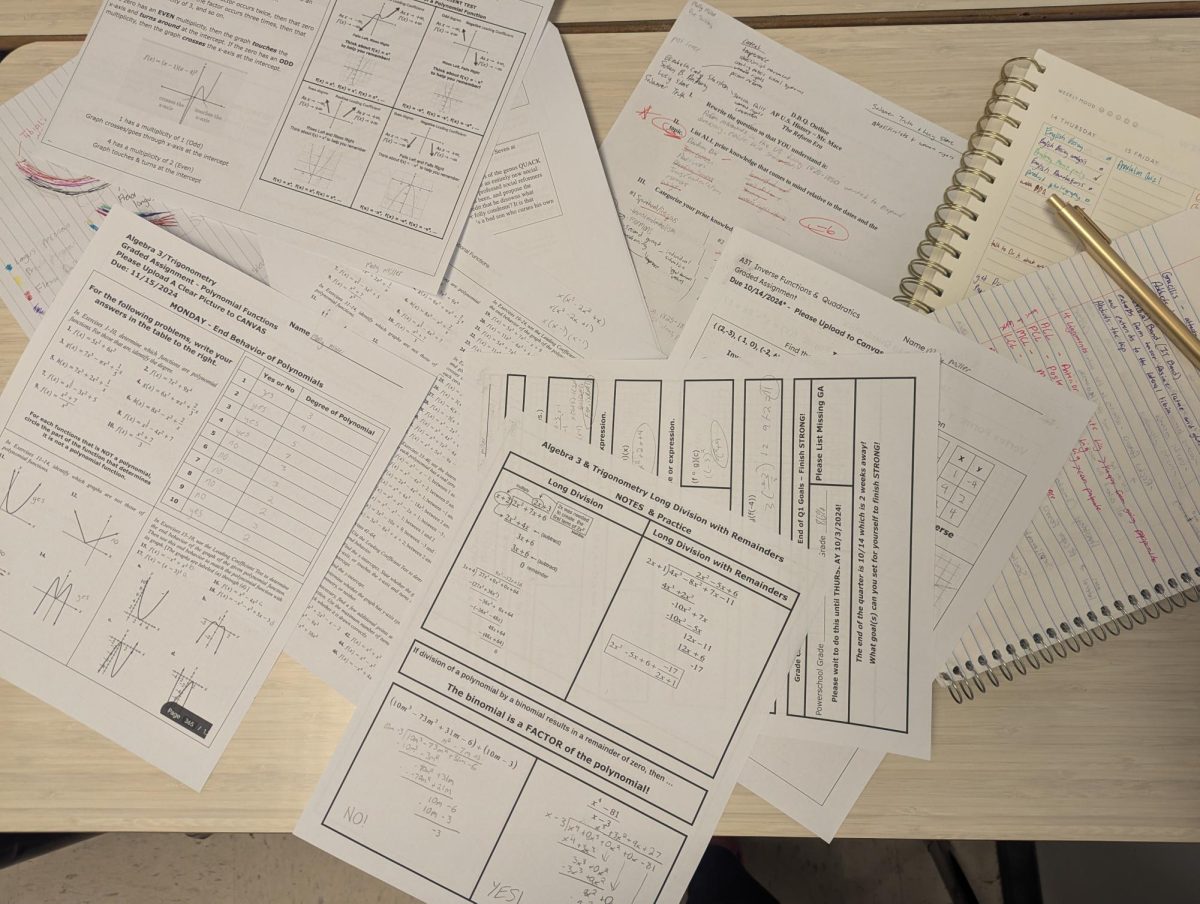

But removing SROs after the pandemic wasn’t just a symbolic gesture. Overwhelming data shows SROs often contribute to the school-to-prison pipeline, where school systems funnel disadvantaged kids into the criminal justice system instead of providing them with support services. One study from the Cato Institute detailed how many problems the SRO system causes. Although the amount of violent fights decreased in most of the schools they surveyed, the Institute reports mostly bad outcomes. “The number of students who were expelled, referred for arrest, and suspended from school skyrocketed”, says the report, and eventually almost all of the schools in the study had a huge problem with chronic absenteeism.

CHS is already struggling with attendance, and adding SROs into the equation would only make these problems worse.

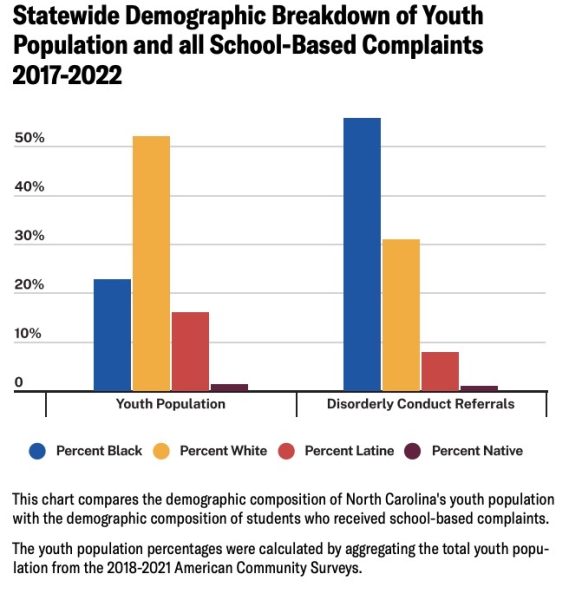

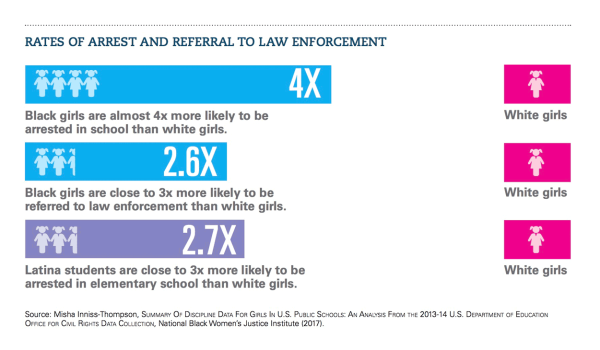

School police officers are also notorious for doling out punishments unfairly based on students’ race and socioeconomic background, which is a huge dividing factor in our school.

Researchers at SUNY Albany who studied how SROs affect schools found that Black students were expelled or suspended from school at over twice the rate of white students. Expulsion and suspension means that “students miss the point of school – to be in the classroom learning – which can create lasting educational and socialization gaps.” Our school already has problems with learning gaps from online learning during the pandemic, and again, SROs would only deepen the divide between students.

CHS was no exception to this racial bias when police officers were stationed here. Dr. Irizarry, who was principal of CHS at the time, gave an interview about school police officers in an earlier edition of The Knight Time Review: “One thing we’re really cognizant of at this school is our perception,” said Dr. I. “We have a diverse group of students from different socioeconomic backgrounds, and from what we’ve heard from our brown and Black students is that the presence of officers alone is triggering.”

Crucially, school police officers made students feel less safe – exactly the opposite of what they’re intended to do. The officers didn’t protect their students from any major fights or dangerous activity, so nothing good came out of their presence in our school.

When SROs were removed from our school the first time, former Mayor Nikuyah Walker released a statement, saying “our public school system is an institution that mimics the prison-industrial complex…and SROs are simply one element that highlights this fact.” As a conclusion, Walker said “we must commit to the creation of a paradigm that replaces this current institution that has continuously failed Black children since desegregation.”

Many alternatives to school police officers would be a better fit here, such as continuing to use our current CSA system or building a more solid relationship with the Charlottesville Police Department without inviting officers into our schools.

Clearly, our school system has played this game before. For five years, Charlottesville supported the school-to-prison pipeline and the racially biased punishments that come with the SRO system. Do we really want to go back?