The Third Factor: Why Grades Hurt Us All

October 13, 2022

Within the politically tumultuous climate that is our world, capitalism is a word commonly thrown around to support a point, insult political opposition, or prove how the West is bathing in freedom. For example, The United States (a highly capitalist nation), as a political and governmental organization, has generally supported the message that everyone with the right motivation and work ethic can be economically successful and/or politically powerful. This idea is called meritocracy. Meritocracy, over hundreds of years, has proven itself to be dysfunctional. Currently, and throughout the course of history, we can see this idea being used to favor certain genders, ethnic groups, races, cultures, or religions. All the way since Tang China, this system has manifested itself as a bigoted parasite. Meritocracy is a lie that has always favored the aristocracy (the rich and powerful ruling class), and has led to the grade system hurting the masses, with this dysfunctional idea being used as its legitimizer.

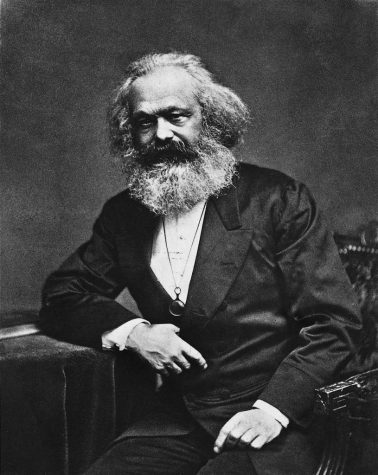

To be clear, capitalism at its most basic definition refers to the socio-economic system currently used in the entirety of the developed world, and arguably used in every single nation worldwide. Major characteristics of this socio-economic system include: private ownership of the means of production (the means of production are simply the tools and materials used to make things), and exploitation of the working people en masse. This system has continually expanded its global dominance for the last 2 or 3 centuries. Another important characteristic is the influence of capitalism in nearly every social institution on earth. As philosopher/economist Karl Marx put it in The Communist Manifesto, “It . . . has left remaining no other nexus between man and man than naked self-interest, than callous ‘cash payment’”. He later says, “The need of a constantly expanding market for its products chases the bourgeoisie over the whole surface of the globe. It must settle everywhere, establish connexions everywhere” (82-83). When he uses the term “bourgeoisie” he is referring to the ruling or capitalist class. These are the people who own the means of production and perpetuate the capitalistic system.

But why should you care? And does this have to do with grades? Well, chances are you aren’t exactly the biggest fan of the grade system. In fact, a survey sent out across CHS indicates that nearly 70% of students believe that we would benefit from an alternative system, and that over 90% of students that submitted the survey feel as though they haven’t directly benefited from the grade system (overall 22.7% said they explicitly haven’t benefited from it.) This, for many people, may be because they’re failing chemistry or the grade system causes them constant stress, which are valid reasons. But there is a far more nefarious side to the grading system.

This’ll get a little bit more complicated for a second, so hang with me here. Karl Marx wrote a series of books called Capital or, in his native language of German, Das Kapital. In Volume 1, Part 1, Chapter 1, The Commodity, he brings to light how and why we use products, a.k.a commodities. He states that a commodity satisfies a human want or need of some kind. If you want to sit around and watch movies on your couch, pajamas might satisfy your desire to be comfortable. Now, every commodity has a “use-value”, which is characterized by the usefulness of this commodity, and the usefulness of a commodity is characterized by its physical characteristics. Commodities also have exchange-values, which is the rate at which two commodities can be exchanged. These two factors are quantitative, so, for example, you could exchange 1 diamond for 10,000 rags. Now, we arrive at the third factor. Marx states that if these use-values are indeed use-values, and if they have an exchange relation with each other, then they are reducible to a third thing.

Okay. Before we go any deeper into the third factor, let’s pause for a sec. So we have two things that are exchanged for each other but differ in amount because of how useful they are (their use-values). Doesn’t this kind of sound like the way we exchange assignments for number or letter grades? Let’s venture back to that diamonds and rags example. Marx would argue that the reason that the diamond has more value is because, in this hypothetical, it took 10,000 times more time to produce than a rag. So you might be led to think that schoolwork usually has a far higher value than any number or letter grade, because it took more time to produce. Well, as Marx put it in Capital, “In order to embody his labor in commodities, he must above all embody it in use-values, things which serve to satisfy needs of one kind or another” (283). A grade has more value simply because the use-value of an assignment is usually nearly nothing, and the price we deem the grade to be at is usually extremely high, because the demand for grades is disproportionately higher than the supply. Basically, if you think of grades as a product, they have a high value, or built-in worth. They also have a high price because of how high the demand is for them (how many people want them vs. how many there actually are) along with the fact that certain people have a monopoly on their distribution (only certain people can give them out).

So what is the third factor? And why is it hurting everybody? Well, the third factor is human labor. According to Marx, commodities have value because they are materialized human labor (someone had to work to make them) and the amount of this value is decided by the amount of labor put into it. This is known as the Labor Theory of Value. We can see it at work if we look at the grade system as an economic one, where assignments and grades are exchanged at an exchange rate. The reason (as we’ve already established) that grades have a higher value than assignments is because assignments usually have very little use-value. Grades turn assignments into mudpies, things that you labor over, but whose use-value is almost nothing (without a grade to exchange for it). Students are effectively turned into laborers, and trained for a lifetime of capitalistic exploitation. This system is forced competition, and this competition has a detrimental effect on the mind of the student.

Along with the capitalistic grade system and the problems it brings, numerous other issues accompany it and the lie of meritocracy. As mentioned before, meritocracy has historically favored certain groups of people, who could use the system to their advantage and dishonestly market their success. Today, the ruling class uses this system to legitimize their rule in capitalist society. Another prevalent example of meritocracy’s malice within the school/grade system is classism. In a 2019 article for Vox, Yale Law professor Daniel Markovits said, “it exacerbates and reproduces inequalities, so that one thing that’s happened is that because the rich can afford to educate their children in a way nobody else can, when it comes time to evaluate people on the merits, rich kids just do better.” He goes on to say, “Meritocracy adds a kind of a moral insult to this economic exclusion because it frames what is in fact structural inequality and structural exclusion as an individual failure to measure up, and then tells you if you’re in the middle class, the reason you can’t get the great high-paying job is because you’re not good enough and the reason that your kids can’t get into Harvard is that they’re not good enough, which is complete nonsense. But that’s what the ideology tells you.” From here we confront yet another flaw in the grading system: the limited supply of A’s. Meritocracy relies on the fact that within it, only certain people can succeed– the success of some is built on the failures of many. This means that the hierarchy of grades (A-F) is designed to keep some people down— it needs to in order for the merit system to function.

Despite the general doom and gloom of this article, there are many positive and viable replacements for the grade system. One system, live feedback, focuses on giving students constructive criticism while they work. This way, when the student finishes any sort of assignment, there’s no need for a number because it’s already their best work. This system works with the student rather than against them, preventing academic burnout. As one student who filled out a survey on the topic said, “Grades are stressful. I’ve always struggled with the grading system because it stresses me out and I feel as though I never learn from it. I’d really appreciate having more actual feedback instead of just seeing a number that tells me how well I did on something.” There are, of course, other ways of looking at meritocracy; I spoke with Econ and Personal Finance teacher Ms. Tewksbury, and here’s what she had to say about merit: “Yes, I believe wealth [is] a factor in the grade system. Wealthier families have more money to spend on private tutors, summer programs, private schools. I would say there is a higher expectation to attend university among elite families. But I have seen plenty of students from every background be motivated and unmotivated towards their education. Ultimately, I’ve observed that academic success comes down to the student’s own curiosity and drive.” Though this viewpoint and Markovits’s disagree on the viability of the merit system, they both recognize wealth as a factor in academic success.

Capitalism has perpetuated the oppression of the masses for centuries. Today the capitalist class uses meritocracy to try to legitimize exploitation and convince the masses that their position is easily moveable, just as the Indo-Europeans in ancient India used the idea of reincarnation to legitimize their oppression of the native people through caste. One can, if they look at the grade system from an economic view, see that capitalism has infiltrated education. So to close, I ask you this: will you allow yourself to be trained for a lifetime of brutal exploitation?