Charlottesville City School’s Trailblazer Day; exploring the history

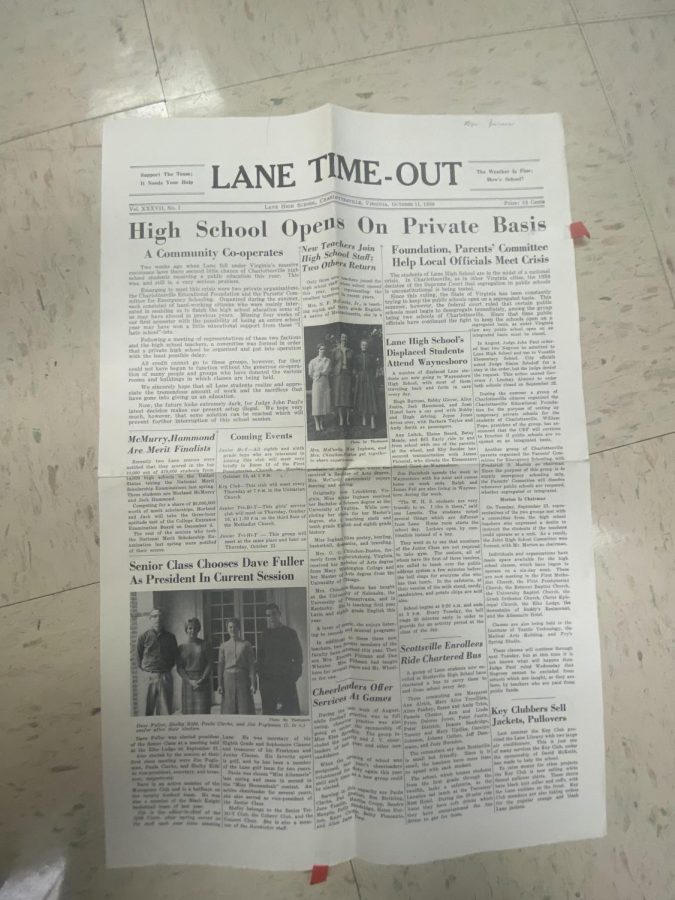

This original 1958 Lane-Time Out Newspaper is first-hand evidence of how Charlottesville used the student newspaper to express to students and staff about the “Massive Resistance” and everything happening around the events of this period.

November 19, 2021

November 18th is Trailblazer Day. Trailblazer Day is a day that honors the first black students to integrate Charlottesville City Schools and the contribution they made to our schools. Only 62 years ago, on September 18th, 1959, 12 brave, black students integrated Lane High School and Venable Elementary School. The year before the first black students integrated into Venable and Lane High School, there was a policy in Virginia (and in many parts of the country) called “massive resistance.” Massive resistance was put in place to shut down schools so they would not be forced to integrate. For a whole year, white Charlottesville students went to private schools and schools outside the county, while black students did not go to school at all. While out of school, “displaced” students from Lane High School still operated their school’s newspaper, but it was called Lanetime-Out, instead of Lanetime. In the few copies of the paper that Charlottesville High School still owns today, we looked through ideas and opinions that were expressed in the newspaper. The one constant thing: the lack of ideas and opinions on integration expressed by students in the newspaper. In this article, we dig deeper into the history of Trailblazer Day and give some background information for people who may not have heard of this type of history before.

As we may know, the Brown versus Board of Education case in 1954 demanded that schools around the country integrate or join together, as they suggested that segregation was wrong and unconstitutional. This also pushed for the outlawing of segregation in other public places too. Because of the Brown versus Board of Education cases and many other cases, newer laws were being made everywhere except for the South. Because of this, multiple families in Charlottesville put their foot down and went to the school board to express their problems with the school system in place. But, because this was in the south, the school board denied the application. According to Dr. Kershner (Venable Elementary Principle),

“The lawsuits ensued, it went to the district court in Charlottesville, and then they tried to appeal to the supreme court. But in 1958, they ordered that Charlottesville integrate. Instead of integration, Charlottesville shut its schools down under what was called ‘Massive resistance.’” This was led by governor Harry F. Byrd Sr., who, at the time, was anti-integration, and pushed for his schools to close. Many of the private schools in Charlottesville that are still seen today were made during this time for the many white kids who wanted a good education during the hardships of not being able to go to public schools. However, much of history, especially in America, tend to leave out black students and people’s opinions and stories. Finally, however, in February 1959, twenty-one brave black students integrated either Lane High School or Venable Elementary School.

As Venable Elementary School was one of the first schools in Charlottesville, Trailblazer Day was originally revolved around the first black students who entered this school in 1959. During this year, the school board allowed 12 students to enter into Venable. According to Dr. Kershner, the current Venable principle,

“They [the black students] didn’t get to go into the building, however, they had to spend their time in the Venable annex which is the short brick building on our playground. It happened to be the superintendent’s office at the time, and that’s where they had school from February until the end of the year.” However, in September of 1959, for the next school year, 9 brave black students walked up the 19 steps of Venable, which started the impactful revolution of integration and Trailblazer Day itself. Mr.Alex-Zan, one of the Charlottesville 12 who integrated Charlottesville City Schools himself, was generous enough to talk to both Zoë and me about his experience of the entire event. Mr.Alex-Zan was seven years old when the integration started,

“I was very excited to attend Venable, I could see it from my house”. He stressed that his mother was the one to take charge, “It was my mother’s idea, I only knew that we had to continue to go to court with the NAACP’s assistance.” He stated, “The Charlottesville 12 parents were the true heroes, so both the parents and students were the Trailblazers.” It seems as if, from our point of view, that there might have been a lot of discrimination, however, there were also moments of pure kindness from both the teachers and students.

“After one student called me ‘Blackie’, my teacher Ms.Miller stated, ‘If you remove the top cover, we’re all the same [underneath].’ She also defended me when a white parent came after me following a confrontation with his sons.” With the help of Ms. Miller and many other teachers and students, Venable was one step closer to becoming one of the most inclusive schools in the area.

During the time before and after integration, Lane high school kept Lantime, the school’s newspaper running. The newspapers from right before and after the Charlottesville 12 integrated Venable and Lane, never mentioned the new, black students in the schools. There are a few mentions of back-to-school, but again, they never specifically mention the new students. One article titled, “Two Students Visit Atlantic City, N.J., Observe Integration” even talks about two student representatives who traveled to New Jersey to see how an integrated school “runs”. Those two representatives quoted in the article seemed to think the school visit went well, with one of the two students named Jon Bailey saying,

“I had a very nice time but was glad to get home. The high school I attended in Atlantic City was one-third integrated, and I thought it ran very smoothly.” Although students definitely had an opinion on integration, their voices are diluted in their articles.

Although Johnson integrated three years later, in 1962, we still also focus on the school during Trailblazer Day. When Johnson was integrated, the City Schools were trying to reduce additional integration into their schools. In between 1959-1962, the NAACP led court cases that challenged discrimination in schools, (such as the black students at Venable that were still segregated in the annex). With the success of the court cases, by 1962 many schools including Johnson, were expanding the process of desegregation. On October 23, 2019, a historic marker was placed by the elementary school, joining the one that was placed at Venable. The marker highlights the history of Johnson, and how it became the third school in Charlottesville and Albemarle county to integrate.

Although it seems like we are a long way from segregation being a part of our lives, segregation was actually very recent. There are countless numbers of people who will stand for the integration of and rights of people of color. According to Mr. Alex-Zan, his mother was one of those people, for she (along with the parents of the other Charlottesville 12) might be the real heroes behind the curtains,

“‘The purpose in going to school is to get the best education and it’s not the color of your skin that’s important, but from the goodness within.’ This [along with discrimination itself] made me more determined to succeed.”

And just like that, with simple but powerful pushes from parents, students, administration, and teachers, these first black students bravely took on the challenge of integrating all-white schools in Charlottesville. By doing this, they set the foundation for schools not only in just Charlottesville, but all throughout the south, for that brought peace between people, and a step towards harmony in America.