Leveling Up Unleveled

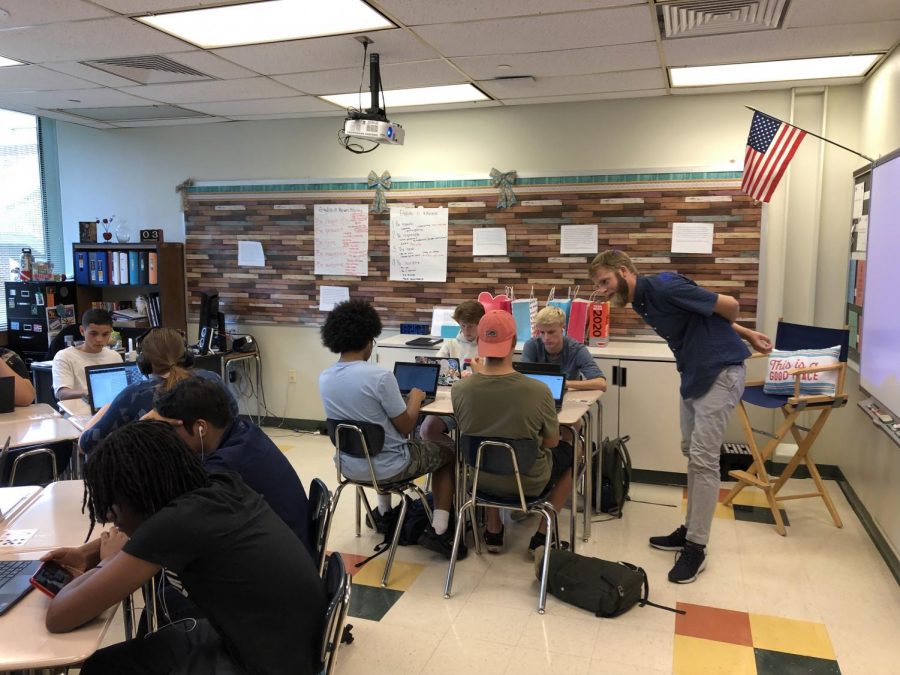

Mr. Josselyn instructs one of his Leveled Up Honors classes. Photo by Charles Burns.

September 18, 2019

For years, the Charlottesville City Schools has been burdened with damning statistics highlighting an intense achievement disparity between students of color and white students. One way of attempting to bridge this gap has been the implementation of “Honors Option” classes in the English department, particularly in ninth and 10th grade. These classes combine students on both advanced and less advanced academic tracks, giving every student in the classroom the option to take the class for “honors” credit, with the only requirement to attain this credit being the completion of certain additional assignments and assessments.

This school year, however, the Charlottesville school system has been significantly magnifying efforts to expand equity in the classroom. Instead of “Honors Option,” Charlottesville High School has implemented “Leveled Up Honors” classes, in which every member of the class is required to push themselves and obtain honors credit.

“If our expectations are low for anybody in this building, then that’s not equitable,” says Jennifer Horne, an English teacher at Charlottesville High School who was an early advocate for “Leveled Up” classes. Mrs. Horne believes that part of the effectiveness of this class format is exposing as many children as possible to a level of rigor and classroom environment that will be able to challenge them, while also giving them the tools to achieve many of the same academic goals as their peers.

When asked about the “Leveled Up Honors” program, Eric Irizarry, the principal of Charlottesville High School, said that the school administration is attempting to answer one pivotal question: “What is the best way to push students and allow students to get more rigor and depth in their learning?”

In addition to the adoption of this class format, there has been a push to utilize “Leveled Up” in all departments, from Math to History, as opposed to just English, where all “Honors Option” courses were previously taught.

“For me, the important distinction is about language and how we think. As we label classes, we respond to classrooms in a certain way. So when we think of all of our classrooms as ‘honors’ classrooms, it sort of changes how we think,” said Zachary Bullock, head of the History department at Charlottesville High School. “The intention is to make sure that we’re providing the same kind of high-caliber education for everybody.”

Despite the staff enthusiasm around “Leveled Up Honors,” there has been some pushback from students. One student called the format “dumb,” saying that she is “being forced to take an honors math class” despite not being strong at math.

Another student asserted that “the implementation of these kinds of courses so late in our education isn’t going to be enough to battle the equality gap” and that efforts to increase equity in education need to be made “before middle school.”

However, some students have reacted positively to this change. Gabby Raubenheimer, an 11th grader who is taking multiple “Leveled Up Honors” classes, has said that “the discussions are really interesting” in these classes. Nic Motley, an 11th grader, has described these classes as a good way to battle the achievement gap that has plagued the Charlottesville school system.

While the long-term effects of “Leveled Up Honors” remain to be seen, it is clear that many around the high school regard its expansion as a positive development for equity and quality of education.